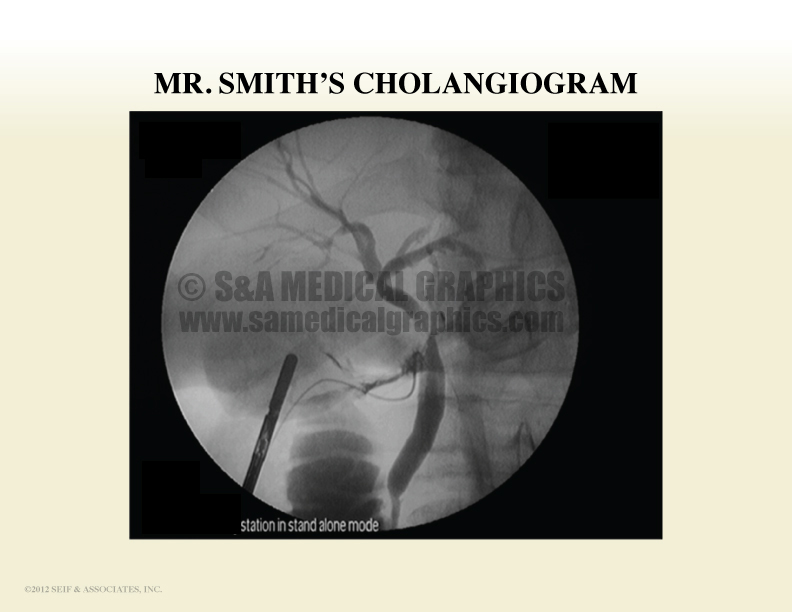

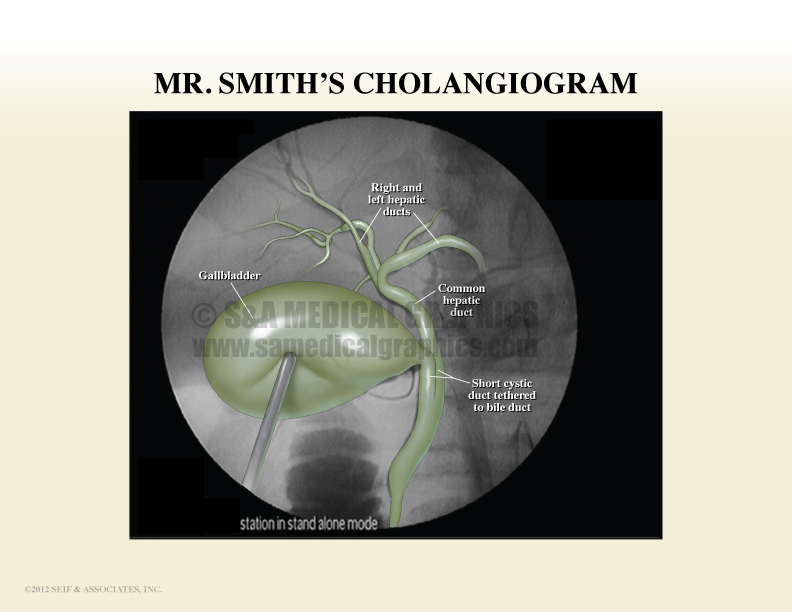

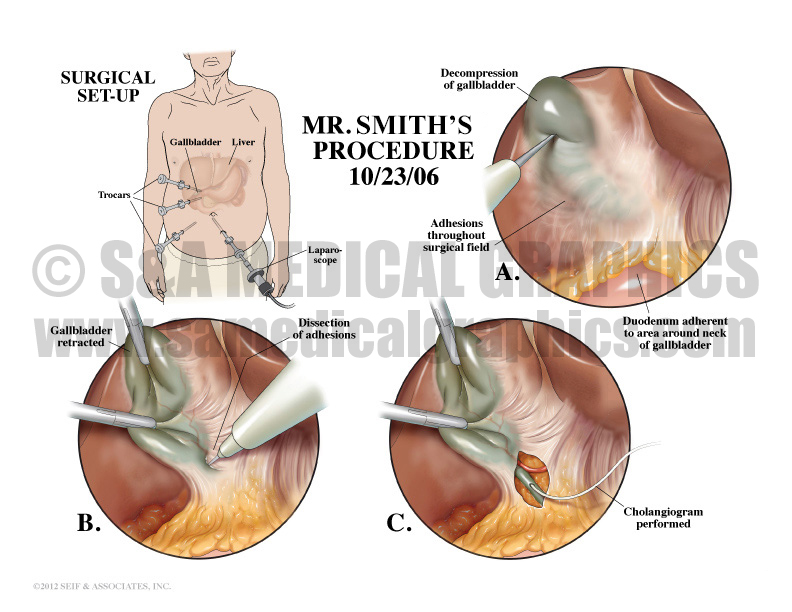

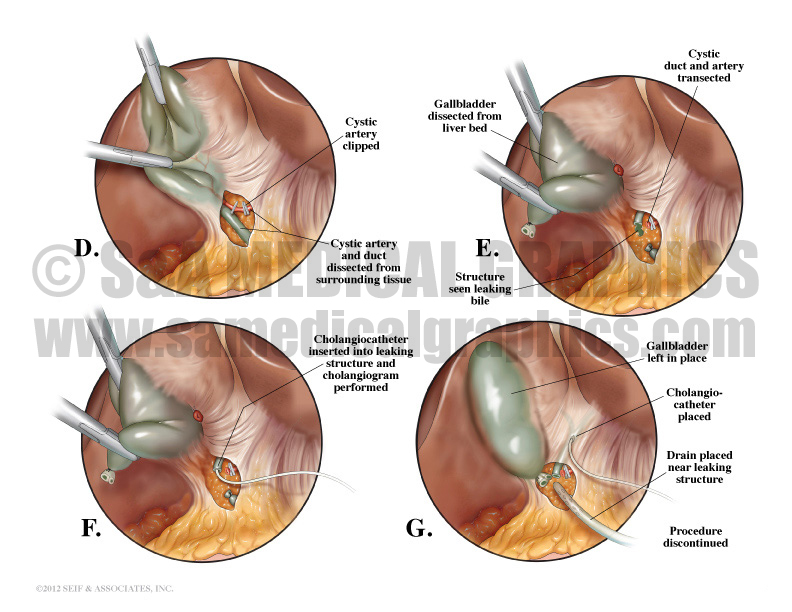

This case involved middle-aged male who presented with multiple gallstones in the gallbladder, one of which was lodged in the gallbladder neck. The defendant performed a laparoscopic cholecystectomy on 10/23/06. Upon visualization of the surgical field, the defendant encountered multiple adhesions, which required tedious dissection. After decompression of the tense gallbladder, the defendant dissected the cystic duct and artery out of the surrounding tissue. An intraoperative cholangiogram revealed a dilated common bile duct and short cystic duct. The defendant then transected what he believed to be the cystic duct but during dissection of the gallbladder from the hepatic bed, he discovered a structure leaking bile into the surgical field. A cholangiogram at that point revealed that the cystic duct had been divided at its junction with the common hepatic duct, resulting in an approximately 3 cm defect in the common hepatic duct.

After multiple consults, the defendant elected to discontinue the procedure and prepare the patient for transfer to another area hospital for repair. A cholangiocatheter was left within the common hepatic duct and a drain was placed in the area of the injury. The trocar sites were closed and the patient was prepared for transfer.

The plaintiff alleged that the procedure was performed negligently, resulting in an injured bile duct. The defense contends that while unfortunate, bile duct injury is a known complication of this procedure, especially in the presence of adhesions. The injury was recognized immediately and plans for repair were made promptly.

The plaintiff alleged that the procedure was performed negligently, resulting in an injured bile duct.

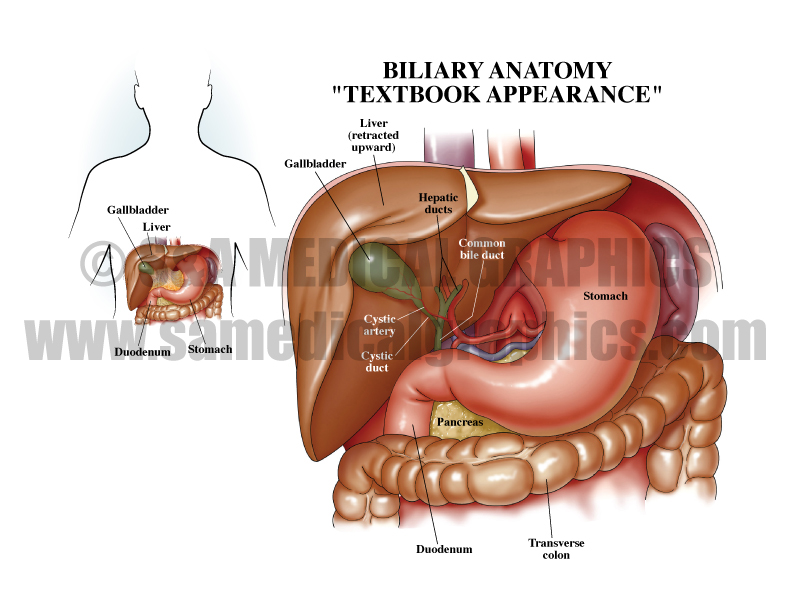

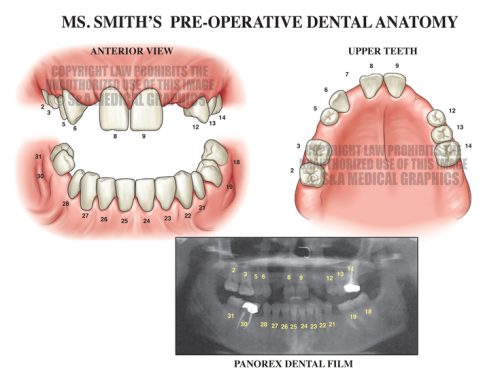

The first step in the visual defense strategy was to educate the jury on the normal biliary anatomy. A simple graphic showing the ‘textbook appearance’ allowed the jury to see and easily understand the anatomy to be discussed during the trial. An overlay image enabled them to better appreciate what the surgeon actually saw upon entering the abdomen, showing that the anatomy is obscured by a sheet of connective tissue and fat—the lesser omentum.

Exhibit 1 depicts the “textbook appearance” of biliary anatomy.

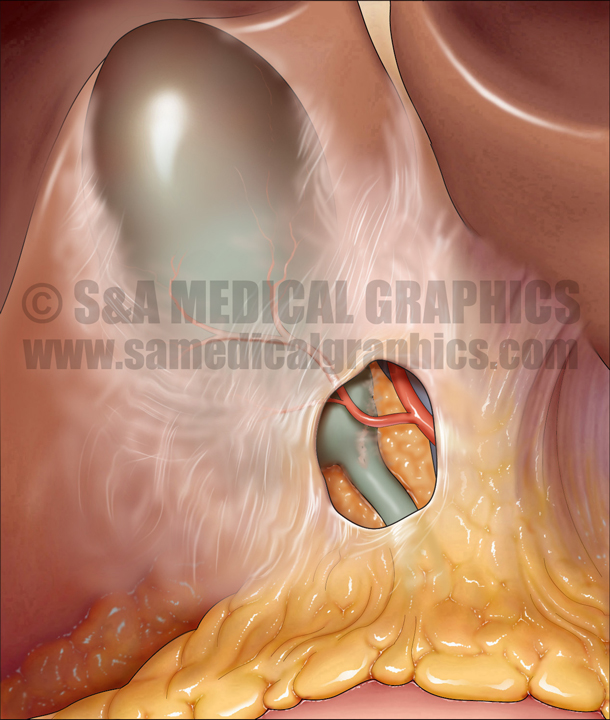

Overlay used in trial depicts the surgical view obscured by the lesser omentum.

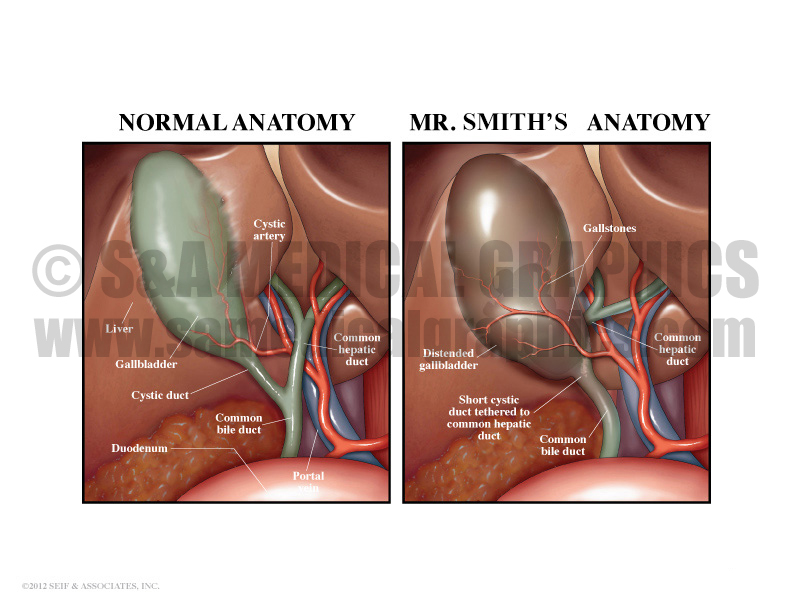

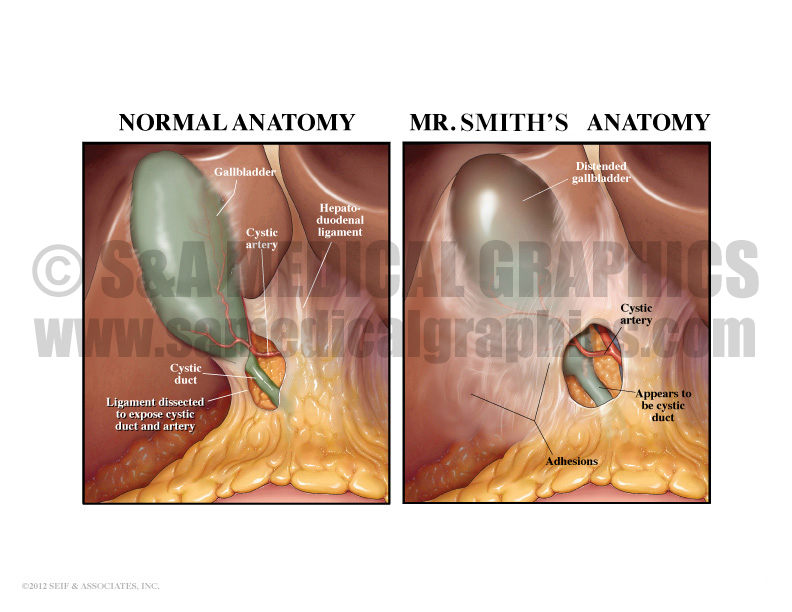

The next exhibit drew the jury into the surgical field in question, showing the normal anatomy in order to compare it to the plaintiff’s anatomy. This clearly outlined the plaintiff’s abnormal anatomy—a short cystic duct that was tethered to the common hepatic duct. A similar image allowed the defense to present the defendant’s surgical view of the plaintiff’s anatomy intraoperatively. This was crucial to the defense by allowing the jury to understand how—although the defendant performed the procedure within the standard of care by dissecting the hepatoduodenal ligament in order to expose the cystic duct and artery—he was unable to appreciate the variation in the plaintiff’s anatomy and subsequently injured the hepatic duct.

Exhibit 2 compares normal anatomy to the patient’s anatomy.

Exhibit 3 compares the surgical view of normal anatomy to the patient’s surgical view anatomy.

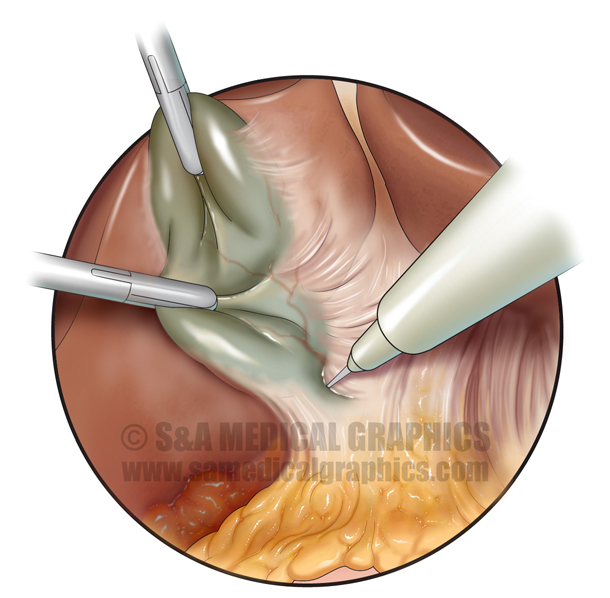

Lastly, a surgical series enabled the jury to see what the defendant did during the plaintiff’s procedure, showing that it was done within the standard of care, and unfortunately, the plaintiff’s anatomical variation resulted in the injury.

Exhibit 5 depicts the laparoscopic cholecystectomy procedure.

Exhibit 6 continues to depict the laparoscopic cholecystectomy procedure.

The visual exhibits used in this case enabled the defense to present the defendant’s story from his point of view and in a very realistic manner. The client felt that they definitely contributed to a defense win in this case!

—Editorial contributed by Emily Ullo Steigler, MS, CMI

—Illustrations contributed by Jennifer C. Webb, MS