The female plaintiff presented to the defendant with abdominal pain and after a sonogram indicated a pelvic mass, the defendant performed an exploratory laparotomy. Intraoperatively, as the defendant entered the abdominal cavity, he used moistened lap pads to position the small bowel up and away from the operative site. The incision was held open with an adjustable retractor in order to expose the pelvic organs. The defendant found a large complex left ovarian mass totally replacing the ovarian tissue, which necessitated a left salpingo-oophorectomy. He irrigated and checked the pelvis, removed the self-retaining retractor and lap pads, and closed the wound. The procedure took only half an hour and just before closure, the nursing staff performed the surgical count for all instruments, sponges, and needles. Both the circulating and scrub nurse indicated that the surgical count was correct twice and the defendant was notified of this.

Postoperatively the patient did well, although she did experience an elevated temperature and some left-sided pain. Tests revealed no abnormalities, but she was started on antibiotic therapy before she was discharged home on post-op day 7. She did well initially, but a little over a month after the surgery, the patient developed an infection in her incision. The wound was cleaned and she was treated with oral antibiotics and she improved.

Two months later, however, she returned with purulence and foul-smelling drainage from her wound. An exploratory laparotomy revealed a subcutaneous abscess that extended into the peritoneal cavity. The abscess contained two retained lap pads. Unfortunately, the patient had a stormy postoperative course with a perforation, fistula, and another abscess.

The plaintiff alleged that the defendant was negligent in leaving two lap pads inside of her during the initial surgery. The defendant contends that he performed a reasonable inspection prior to the closure of the peritoneum. The nurses reported a ‘good count’ to him and recorded the correct count in the chart.

The plaintiff alleged that the defendant was negligent in leaving two lap pads inside of her during the initial surgery.

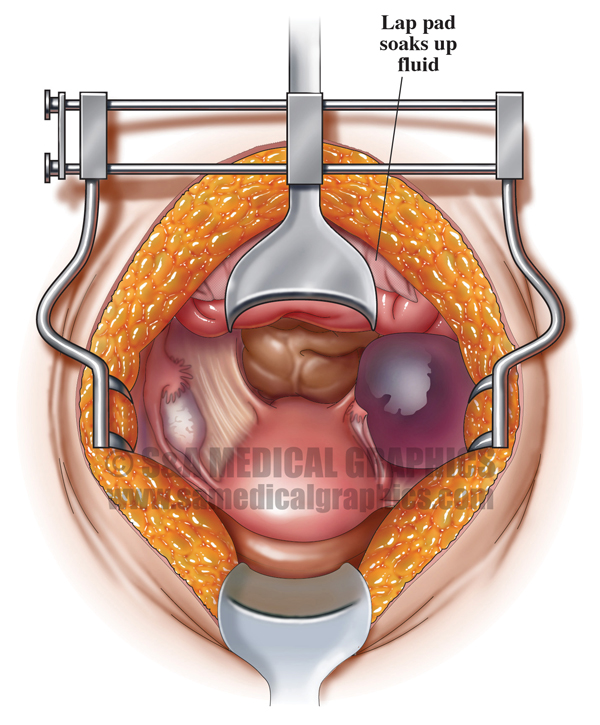

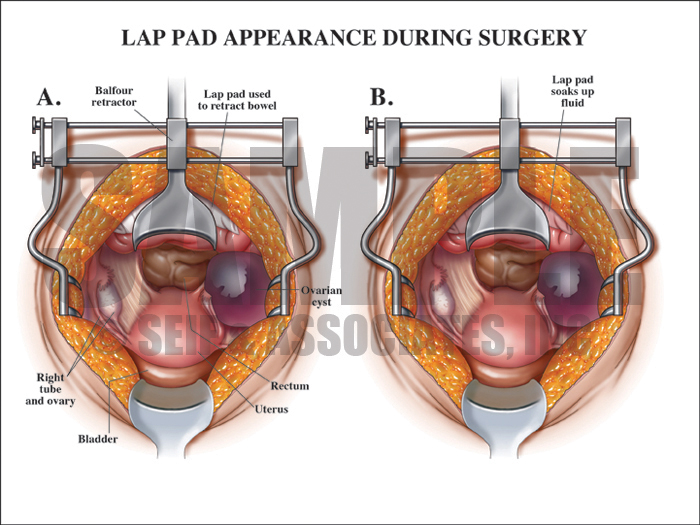

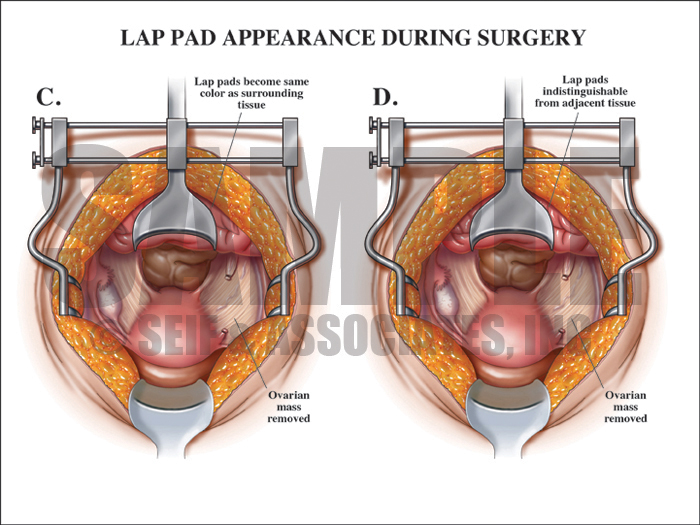

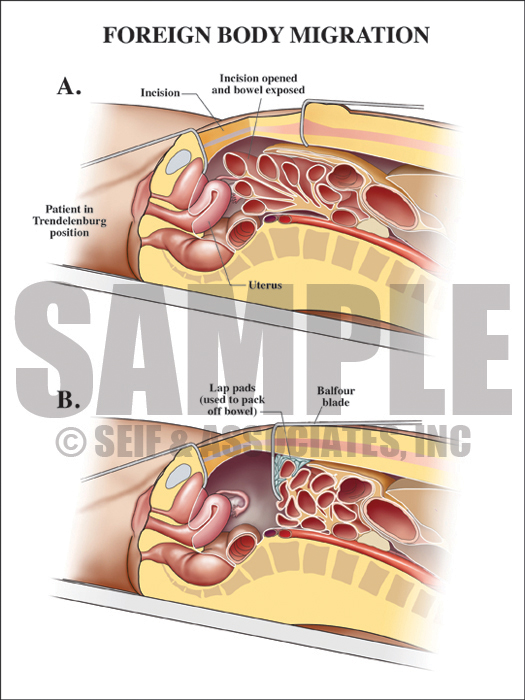

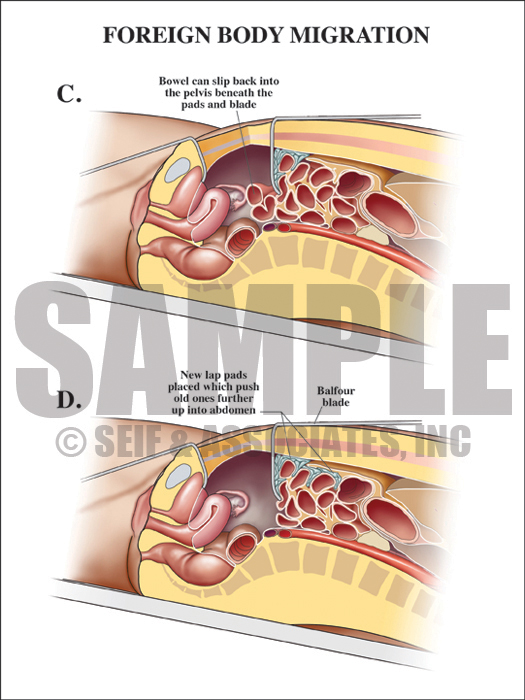

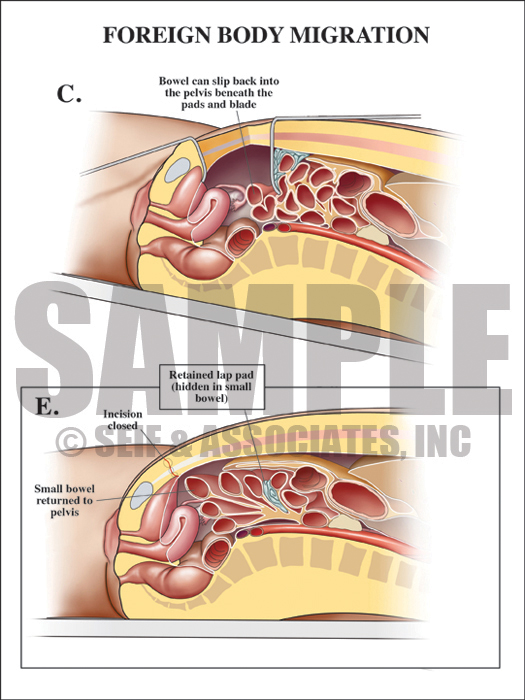

The first step in the visual defense strategy was to help the jury to understand the surgical field and the anatomy that the defendant encountered in this patient in order to explain how this mistake could have happened in the absence of negligence. These images allowed the defense to explain why lap pads were used during this surgery as well as how those pads changed in appearance during the course of the surgery. An overlay showed the jury how, as the pads soaked up body fluid and became matted to the intestines during the course of the surgery, they became indistinguishable from the surrounding tissue.

Exhibit 1 depicts the surgical field and anatomy of the patient.

Overlay visualizing how the lap pads became indistinguishable from the surrounding tissue.

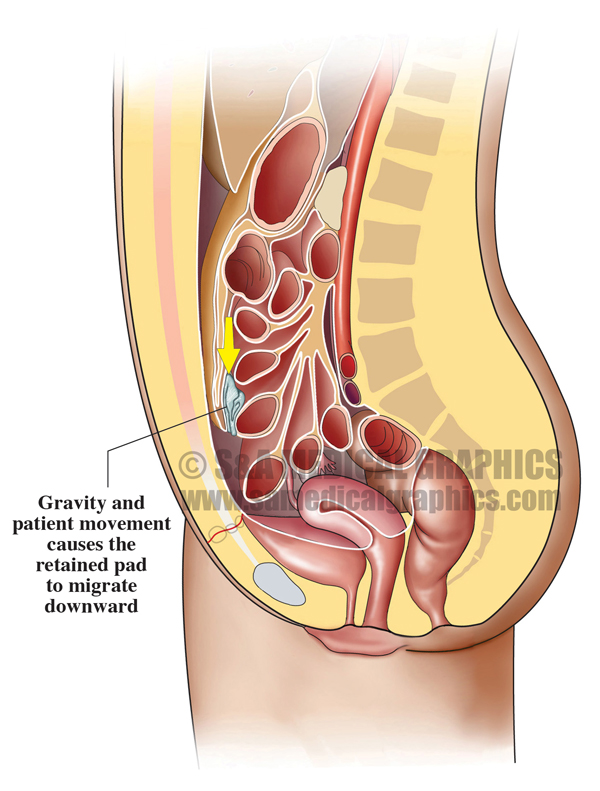

Similarly, the next series of images designed for this case sought to explain to the jury how these lap pads migrated into the intestines during the course of the surgery and were not immediately apparent to the surgeon when he inspected the field before closure.

Exhibit 2 depicts lap pad placement during surgery.

Exhibit 3 depicts lap pads pushed further into abdomen.

Overlay used to visualize how lap pads can become hidden.

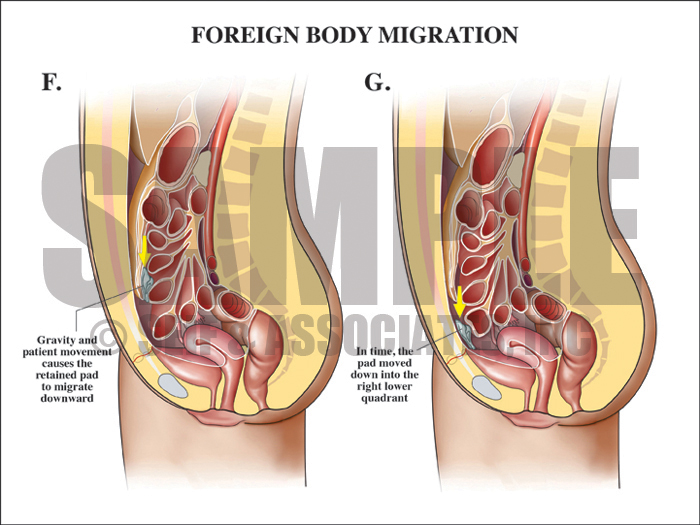

Another area of liability in this case was the fact that the retained lab pads were later found in the right lower quadrant, which was not the area in which the defense contended that they disappeared. The last part of the visual defense strategy for this case was to explain to the jury the concept of foreign body migration and to show how gravity and patient movement caused the pads to move downward in the body.

Exhibit 4 depicts foreign body migration steps.

—Editorial contributed by Emily Ullo Steigler, MS, CMI

—Illustrations contributed by Robert Edwards, MS, CMI